Film is most frequently perceived as a visual medium, but as William Whittington has stated “sound is half the picture.” Sound has the ability to inscribe meaning into a film. Randy Thom, a sound designer for Disney has stated that, “Sound may be the most powerful tool in the filmmaker’s arsenal in terms of its ability to seduce. That’s because ‘sound,’ as the great sound editor Alan Splet once said, ‘is a heart thing.’ We, the audience, interpret sound with our emotions, not our intellect” (Thom, Machinery Aimed at the Ear). Animation can utilize sound techniques to suggest, heighten, diminish, describe, exaggerate and evoke meaning into a film. This paper will explore sound theory in animation, using Disney as a case study for their innovations of sound in animated films and sequences from the film The Incredibles to demonstrate specific uses of sound.

Disney is credited as being the first to use sound-on-film techniques for the animated short, Steamboat Willie in 1928. Prior to this, films were often accompanied either by sound which was recorded separately, or with live accompaniment. To produce the sound for Steamboat Willie musicians recorded the music as they watched the pre-produced film strip. They “synchronized sonic motifs to visual depictions of Mickey Mouse” and thus produced the first embedded soundtrack (Hanna, 2008). This technique of matching animation synchronously with music was later termed “Mickey Mousing.” Later Disney films, such as The Jungle Book (1967) reversed this process by animating the characters to match the musical accompaniment. Characters mouths were animated to match the musicians who sang the songs. Suzie Hanna wrote, “Whether led by visual or audio content, a symbiotic relationship between animator and composer, as well as animator and performer, was established as soon as the technology allowed it” (Hanna, 2008).

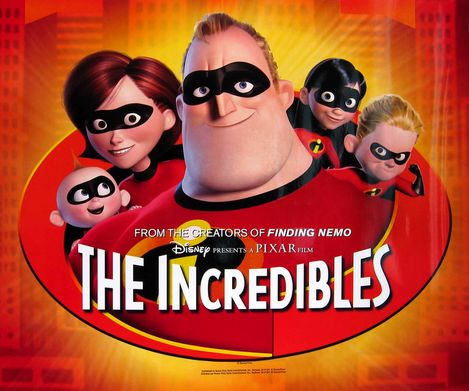

Director Brad Bird has stated that The Incredibles (2004, Brad Bird) is meant to reflect the difference between “the fantastic and the mundane” and it can be argued that this the contrast is most apparent through the use of sound. The film is contrasted with calm, quiet scenes of everyday suburban life, juxtaposed with loud, action scenes of the life of the “fantastic” superheroes (Incredibles DVD).

The Incredibles is an interesting example of sound in animation as it incorporates both competing models of cartoon sound: Abstract Exaggeration and Greater Realism. What Bird described in The Incredibles as the fantastic versus the mundane. The film can be separated into two different aspects of life; average life at home, school and work; and the exciting life of superheroes and the characters alter-egos. Sequences such as a family dinner or the father at work tend to use the greater realism model of sound; the sound effects in these sequences resemble sounds that could realistically be audible in these situations. Following the model of early Disney feature length animations. Many of these scenes do not contain non-diegetic music, another technique which adds to their realistic quality.

The superhero sequences on the other hand require substantially more sound effects, frequently using the abstract exaggeration model. Due to the characters superpowers, hypothetical sounds are needed to convey aspects that could otherwise not be represented, such as the sound of Elastagirl as she stretches. These scenes also contain music for a more dramatic effect, unlike the scenes at home and the father’s office. This is likely a conscious effort on the part of the sound designers, to keep some scenes quiet and realistic to reflect the normal (boring) life of the characters, and contrast this with the fantastic, overwhelming lifestyle of the characters as superheroes.

It is perhaps essential to differentiate between the use of sound in live-action films and animation for the purpose of this paper. Synchronized sound in live action film has an indexical connection; since it is impossible for the relationship of sound and image in animation to be indexical, it is represented iconically (Wright, 2007). This distinction is becoming blurred as animation and live-action techniques are used in combination more frequently. Lev Manovich writes that CGI technologies are redefining the very nature of cinema. Cinema was born from animation, hand drawn images were animated manually prior to the invention of film. The two trends diverged however as theorists began defining and analyzing film as a “lens based recording of reality.” Cinema as defined by Manovich became an art of the index; an attempt to make art out of a footprint. Animation, on the other hand, “Foregrounds its artificial nature, openly admitting that its images are mere representations” (Manovich, 2002).

CGI has developed insofar as believable representations of reality, or hyper-real images can be manufactured using pixels, rather than operating as a copy of an original image. Manovich writes, “Consequently, cinema can no longer be clearly distinguished from animation. It is no longer an indexical media technology but, rather, a subgenre of painting” (Manovich, 2002). While not a Disney film, Beowulf (2007) is a modern example of hyper-real digital imagery in cinema. The characters were created using CGI technology, while resembling the actors voicing each character. As the distinctions between animation and film blur, and their definitions shift, sound theory will soon have to adapt to these changes as well.

Sound in The Incredibles employs both competing models of animated sound; leaning towards that of greater realism common of Disney films since Snow White; while also employing elements of abstract exaggeration. The mundane “normal” life of the characters as well as a majority of settings within the film, implement a realistic implementation of sound. Due to the nature of the film and the superheroes’ powers, methods of abstract exaggeration have been incorporated, such as the sound of Dash’s super speed and Helen’s stretchiness.

“Voices, Music, and Sound Effects [in the greater realism model] are used in a more conservative manner, reflecting live action cinema and the continuity system. While narratives retained elements of fantasy, the image and sound track respects the codes of reality” (Wright, 2007). In 3-D animated films such as those produced by Pixar, sound breathes life into lifeless images. Voices add tone, texture, and personality. Music highlights drama, enhances pace, and sets tone. Sound effects add mass and weight to drawings and computer generated images (CGI). Michel Chion describes this technique as rendering sound… Although animated images are modeled in three dimensions with shadow and light, they remain relatively flat creations…Sound needs to convey if something is hollow or heavy in an animated context. (Chion, 1994). In The Incredibles music and voice intonation are the methods employed to depict the appropriate emotion, while sound effects “give life” to the images on the screen. This again relates to sounds of Helen’s stretchiness and Dash’s super speed, as they are represented through sound. These accompanying sound effects don’t just support the action but they add to its overall effect as well.

Disney’s first feature length film Snow White and Seven Dwarfs (1937) attempted to realistically depict human characters (also attempted in The Incredibles, Disney’s first all human 3D animation). In order to capture a sense of realism they had a dancer pose in the studio so they could capture her fluid movements realistically for Snow White’s character. Disney also wanted to incorporate realistic sound. He had a particular voice in mind and auditioned several singers to find a “mellifluous, sweet and youthful voice” that would suit the character he envisioned. Another key element was music. Disney wanted to use music in a new way within a narrative film. He wanted to “weave it into the story so somebody doesn’t just burst into song” (Jackson, 1993).

Randy Thom provides a useful and lengthy list of the ways in which sound can be utilized within film in his article, “Designing a Movie for Sound.” He states, “Music, dialogue, and sound effects can each do any of the following jobs, and many more: suggest a mood; evoke a feeling; set a pace; indicate a geographical locale; indicate a historical period; clarify the plot; define a character; connect otherwise unconnected ideas, characters, places, images, or moments; heighten realism or diminish it; heighten ambiguity or diminish it; draw attention to a detail, or away from it; indicate changes in time; smooth otherwise abrupt changes between shots or scenes; emphasize a transition for dramatic effect; describe an acoustic space; startle or soothe; exaggerate action or mediate it” (Thom, Designing).

Thom employed many, if not all, of these methods within The Incredibles. He used sound techniques to allow the audience to know what characters were feeling at various points within the film; and to separate what Brad Bird called the fantastic from the mundane. This first idea is perhaps the most important distinction, as all members of the superhero family go through various emotional changes throughout the course of the film, and these emotional changes may not be as readily apparent, or possible to portray without the implementation of sound. Mary Ann Doane has explained, “Sound and image are used as guarantors of two radically different modes of knowing (emotion and intellection),” and “sound and image, ‘married’ together, propose a drama of the individual, of psychological realism” (Doane, 1985). We can get a better understanding of the characters as both sound and image can reflect different character traits.

Sound can provide a different meaning than the image, but most commonly within Disney animations, the sound is working to reinforce and heighten the meaning that is being presented within the image. The scenery, lighting, color scheme, facial expressions and sound of these animated films all have to be created, and all work together simultaneously to invoke various meanings. Doane’s quotation here is not referring to animation, as she says the image can be taken as a representation of reality, but it is important to understand that the sound can provide meaning that may not be apparent in the image itself. Michel Chion described the relationship between sound and image by suggesting, “The image is the projected and the sound is the projector, in that sense the latter projects meanings and values onto the image” (Chion, 1994).

Disney Studio was responsible for many innovations to animation. Such as the first feature length animation (Snow White), the first sound-on-film animation, as well as the first Technicolor animation. Disney is also notable for its experimental sound techniques. Fantasia, although not successful commercially, was an attempt to make a feature length film animated to music. Rather than following a narrative, the film acts more as an animated concert. Disney also produced the animated short series Silly Symphony which had animated images and music operating in synchronization. Walt Disney saw the primary technique of animation as “bringing images to life,” he demanded a sense of ‘naturalness’ in his animations. He saw animation as needing to convey an “illusion of reality” and music as already having a life of its own (Brophy, 1991). The challenge lied in attempting to bring these two aspects together; the artificial nature of the illustrated image, and the organic nature of sound. Ernest Walter has said, “Music is used to create an atmosphere which would other wise be impossible...Often, it is an augmented effect blending with dialogue so that one is almost unaware of its musical presence, yet adding so much to the value of the scene” (Thom, Designing).

Both music and voice intonation can represent various emotions of characters within animation. Brad Bird, when discussing The Incredibles said, “The thing that amazes me about music is that in a certain way it’s not specific, but emotionally it’s completely specific” (Incredibles DVD). Randy Thom when describing music in animation said, “A well-orchestrated and recorded piece of musical score has minimal value if it hasn’t been integrated into the film as a whole…Sound, musical and otherwise, has value when it is part of a continuum, when it changes over time, has dynamics, and resonates with other sound and with other sensory experiences” (Thom, Designing a Movie for Sound).

A scene which invokes a strong sense of “feeling” in The Incredibles is when Elastagirl and Mr. Incredible are first shown interacting on a rooftop near the start of the film. This sequence employs both music and voice intonation to reach the desired effect. As Walter Murch has described, “Music [unlike speech] is sound experienced directly, without any code intervening between you and it. Naked. Whatever meaning there is in a piece of music is ‘embodied’ in the sound itself. This is why music is sometimes called the Universal Language.” (Murch, Dense Clarity - Clear Density). He goes on to explain that there are musical elements that can work their way into almost all speech; you can tell by the tone of someone’s voice; how they say something; what they are feeling; whether they be happy or angry. In this scene the audience can instantly recognizable that the two characters are attracted to one another due to their tone of voice and other sound implementstions. Elastigirl speaks in a slow seducing tone, and the non-diegetic music accompanying the scene is a romantic jazz number. To further the effect, Mr. Incredible whistles his interest as Elastigirl departs, and there are “whimsical” sound effects playing in the background, connoting the idea of love. The image adds to the effect by showing the two characters close together, under golden lighting as the sun sets.

Mary Ann Doane writes, “The ‘value’ alluded to remains unexplained…the concept is inaccessible to language, to analysis, or to intellect understanding. Sound is a bearer of a meaning which is communicable and valid but unanalyzable” (Doane, 1985). In this particular scene, the sound is deceiving the audience because it seems to suggest the two characters are casually flirting, especially in terms of the dialogue, as Elastigirl coyly tells Mr. Incredible she is busy later that night and can’t go on a date with him; and we soon discover they are fiancés and their wedding occurs that very evening. This is an example of sound adding meaning to an image that may not be possible in silence. Randy Thom described this effect in “Designing a Movie for Sound,” “We know that we want to sometimes use the camera to withhold information, to tease, or to put it more bluntly: to seduce. The most compelling method of seduction is inevitably going to involve sound as well” (Thom, Machinery).

It would be inadequate to discuss sound in The Incredibles without referring to the sequence known as “The 100 Mile Dash,” in which the character Dash first realizes how fast he is capable of traveling (one of the emotional changes discussed earlier). This realization comes about because of the danger he is faced with in the form of a terrifying and high-speed space ship. Randy Thom discussed how this effect was achieved in an article in the “San Francisco Chronicle,” he says, “We have enormous latitude in an animated film to create this sonic world from zero. And we have a whole palette of sounds we can use to create a mood. We can make it seem sinister or light.” Referring to the sound of the velocipods he says, “This is a sinister sound -- something that the character Dash hears. He's being chased by these flying saucer-like things called velocipods. When I began to do the sound for this, I thought about what things in the world are fast, and sound fast. There are jets, rockets, race cars. And I thought, race cars might work -- they sound high tech, and they make a revving sound when they prepare to go fast; you can't do that with a jet engine. I started listening to all the samples we have in our library of race car sounds and chose one. Then the trick is to fiddle with it, so that when the audience is sitting in the theater they’re not thinking, where’s the race car? I’m hearing a race car!” (Ganahal, 2005). In The Making Of portion of the DVD he goes on to say that to make these vehicles sound dangerous he added the sound of knives rubbing against each other and than slightly distorted them. This sound explains to the audience how dangerous and fast the velocipods are. The music that accompanies this scene is a kind of frantic, fast paced xylophone as Dash runs away, which gets slower, deeper and more terrifying, through the use of trombones and other instruments when the velocipods get close to him. Dash’s speed is also accentuated by the accompaniment of quick, light sounding footsteps. The music in this sequence has the effect of speed, urgency, danger, and triumph as the plot progresses.

Randy Thom has discussed a similar idea to this in reference to sound in action and sci-fi films, He wrote. “You begin by trying to forget for a while what the Nazi tank in an Indiana Jones film would “really” sound like, and start thinking about what it would FEEL LIKE in a nightmare. The treads would be like spinning samurai blades. The engine would be like the growl of an angry beast. You then go out and find sounds that have those qualities, or alter sounds to make them have those qualities. It makes no difference whether the sounds you collect actually have anything to do with tanks, samurai blades, or growling animals. The essential emotional quality of the sounds is virtually ALL that matters” (Thom, Designing). This idea is especially important in relation to The Incredibles because it is an animated film, it does not have to be represented as reality insofar as live action films do. Sound designers are left with more potential to influence the “feeling” and emotional qualities of sound as they are freed from attempting synchronized indexicality.

In “Designing a Film for Sound” Thom wrote about the use of sound to give a sense of a particular location. He says it is possible to “produce a set of sounds which range from banal to exciting to frightening to weird to comforting to ugly to beautiful. The place can therefore become a character, and have its own voice, with a range of ‘emotions’ and ‘moods’” (Thom, Designing). Within The Incredibles the costume designer known as “E” has a very large home, and when the characters speak in this location you can get a sense of its size through an echoing caverness quality to the characters voices and footsteps.

The Incredibles employs various techniques through sound to suggest, define, heighten, diminish, describe, exaggerate and evoke meaning onto the images within the film. As an animated film, sound becomes essential to provide meaning and give life to the otherwise lifeless image. Sound in The Incredibles is used to expose the emotions of the characters and assists in portraying the inner changes each character experiences the film. The sound techniques help show the strengthening of the parent’s relationship, the fathers growing happiness as he returns to the life of superhero, and the children’s emotional changes as they became more conscious of their powers, and more aware of themselves as individuals.

Various sounds help to differentiate the contesting aspects of The Incredibles, the opposition between the fantastic and the mundane. Sound can heighten the dramatic effect or diminish it when appropriate for the plot. In addition, sound can give the various locations within the film their own mood and emotional qualities. As many theorists have explained, sound makes its appeal on the senses of the spectator while the image aims more at the intellect. It is sound which adds real meaning to the film. As Randy Thom stated in The Making Of portion of The Incredibles DVD, “People sometimes say that film is a visual medium, but in fact it really doesn’t function without sound.”

Bibliography

Brophy, Philip. “The Animation of Sound.” Illusions of Life. Ed. Alan Cholodenko. Sydney: Power Publications. 7-112.

Chion, Michel. “Sound Film- Worthy of the Name.” Audio Vision: Sound on Screen. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994. 141-156.

Doane, Mary Ann. “Ideology and the Practice of Sound Editing and Mixing.” Film Sound: Theory and Practice. Eds. Elisabeth Weis and John Belton. New York: Columbia University Press, 1985. 54-62.

Ganahl, Jane. “With an ear for storytelling, Randy Thom makes the audience believe what they hear.” San Francisco Chronicle. 22 Feb. 2005: E-1. 30 Nov. 2008.http://www.sfgate.com/cgibin/article.cg?file=/c/a/2005/02/22/DDGSHBDIAV1.DTL

Hanna, Suzie. “Composers and animators – the creation of interpretative and collaborative vocabularies.” Journal of Media Practice. 2008. Vol. 9: 1.

Jackson, Kathy Merlock. “Walt Disney: A Bio-Bibliography.” Westport: Grenwood Press, 1993.

Manovich, Lev. “Digital Cinema and the History of a Moving Image.” The Language of New Media. Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2002. 293-308.

Murch, Walter. “Dense Clarity-Clear Density.” 30 Nov. 2008. http://www.ps1.org/cut/volume/murch.html

Thom, Randy. “Designing a Movie for Sound.” FilmSound.org: Learning Space dedicated to the Art and Analyses of Film Sound Design. 30 Nov. 2008. http://www.filmsound.org/articles/designing_for_sound.htm

Thom, Randy. “The Machinery Aimed At the Ear.” FilmSound.org: Learning Space dedicated to the Art and Analyses of Film Sound Design. 27 Nov. 2008.http://www.filmsound.org/randythom/machinery.htm

Wright, Benjamin. “Animation.” FILM 3901 (B). Carleton University. 5 Nov. 2007.

Fon Perde Modelleri

ReplyDeleteNumara onay

vodafone mobil ödeme bozdurma

Nftnasilalinir

ANKARA EVDEN EVE NAKLİYAT

trafik sigortası

dedektor

Https://kurma.website/

ASK ROMANLARİ

ümraniye beko klima servisi

ReplyDeletependik beko klima servisi

tuzla lg klima servisi

tuzla alarko carrier klima servisi

tuzla daikin klima servisi

çekmeköy beko klima servisi

çekmeköy mitsubishi klima servisi

maltepe bosch klima servisi

tuzla toshiba klima servisi

Good content. You write beautiful things.

ReplyDeletetaksi

korsan taksi

mrbahis

vbet

sportsbet

vbet

hacklink

mrbahis

hacklink

Good text Write good content success. Thank you

ReplyDeletekralbet

poker siteleri

slot siteleri

bonus veren siteler

kibris bahis siteleri

tipobet

betpark

mobil ödeme bahis

burdur

ReplyDeleteedirne

erzurum

ordu

kilis

LNX3J

antep

ReplyDeletehatay

kocaeli

tokat

uşak

LTK26

salt likit

ReplyDeletesalt likit

LM1KZ

kasmalı oyunlar

ReplyDeleteresimli magnet

silivri çatı ustası

çerkezköy çatı ustası

referans kimliği nedir

643VJ